Part 24 – Life on a West Coast Farm in the 1920s Children never at a loss to devise their own fun Dick O’Callaghan and Leslie Walker (nee O’Callaghan) – 21/09/01

|

|

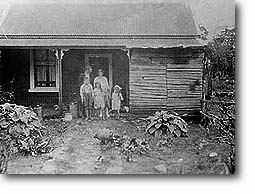

| From left to right Leslie, Dick and Eileen O’Callaghan at the front entrance to the farmhouse Photo source Leslie Walker (nee O’Callaghan) |

Dick tells of the games that filled his free time on the farm. As the land was so sparsely populated, we felt we had it at our feet and could travel anywhere and everywhere within a radius of a few miles without fear of trespassing. Strangely we never felt lonely, and were always able to find things to do to keep ourselves occupied.

Down to the beach From our house we often walked through the bush down to the shingle beach at the back of our property. To reach the beach we made use of an old rusty ladder, permanently bolted to the rock cliff face, but we could not use it at high tide without getting wet feet. There was no need to fence the bottom of the farm as our animals found the sheer cliff faces impossible to negotiate. Still, we did lose an occasional cow when it grazed too closely to the edge and lost its footing. In such cases it had no hope of surviving the fall.

The beach itself was quite steep, and there was a very severe backwash. It was extremely dangerous to be caught in this, and swimming there was quite impossible. We spent many happy hours playing on that beach and exploring the caves there, some of which gave evidence of Maori occupation in earlier days.

Sometimes we managed to capture a few crayfish among the rocks in the pools at low tide. Once we caught a small octopus and used it as a football, kicking it up and down the beach for a couple of hours. The poor thing was still alive when we left, and we didn’t even bother to throw it back in the water. Perhaps the tide came in and rescued it before its life ticked away, but, even so, I imagine its recovery would be extremely doubtful. Actually we were quite amazed at its ability to squirm through a fishing net considerably smaller than the animal’s body.

Exploring the bush Many of our leisure hours were spent exploring the bush. At certain times of the year rata and clematis blossoms added to its beauty, but it wasn’t until later years we realised that, as children, we didn’t really appreciate it. I suppose we took it as a matter of course. We climbed trees and built houses in them, robbed birds’ nests and caught fresh water crayfish under the rocks in the creeks that ran through the bush. Fully grown, these would have been about five inches long, I suppose, and we cooked them over an open fire at the creek side. We boiled them in water in a tin we had the foresight to take with us. They were really good eating, but sadly became very scarce because our scavenging gave little scope for the females to breed sufficiently well to keep the population up.

Another use of the forest was to make swings utilising the supplejack vines growing up the trees. We would select a vine well attached to a large tree overhanging a gully. This we would cut at ground level, making sure that it was well attached to the top branches of the tree. All was now ready, and grasping the vine in our hands we would push off and swing out across the gully, and, hopefully, back to the tree. It was great fun as long as the vine brought us back to land and didn’t leave us swinging helplessly over space. However, a trial with the empty vine gave us a clue, and, if we were unable to get back to land, we attached a long string to it and were able to bring the ‘swinger’ back by that means. Hanging on to the vine was hard on the hands and often produced blisters, despite the fact that our hands were well hardened with farm work.

Adventurous, sometimes dangerous, games There were many other activities to attract our attention. One of these was to play “Cowboys and Indians”, and of course we had to have bows and arrows. The bows were made from green supplejacks which were in plentiful supply, and which, when bent to about 45 degrees of a circle and held there with strong string, were surprisingly effective. Arrows were obtained from the seed stem of the toi-toi plant, and, loaded with a 3 or 4 inch nail in the top to give added weight, were quite lethal. We would often play “chicken” by speeding the arrows skywards and dodging them as they fell to earth. When firing them at one another we dodged behind large rocks, as it was a dangerous game and we had to be careful. We made targets and had competitions in accuracy. I can’t remember that any of us were ever hit, but much to my dismay, I did once manage to hit and kill a waxeye. On seeing the body I burst into tears; to a child of my age it was a pitiful sight.

Another dangerous weapon we used was the “shanghai”. A forked stick and rubber were used in its making, and it could propel small stones quite a distance at remarkable speed. We made darts out of flax and had great fun sending them off from the cliff tops, and watching them float down to the beach below. The further out on the beach the dart flew, the greater the prestige of the one who made that particular dart.

Probably the most useful feature of the flax was its use as a replacement for string. From it we also made stockwhips. To do this the flax was stripped to within about nine inches of its length, and this, firmly tied to a circular stick of approximately the same length, formed the handle. The stripped part was then divided into two and mostly twisted, (it could be divided into three and plaited), then tied at the end. Often we would make it longer by adding further strips of flax to the twist at intervals. A lash, also of flax, was then attached and the whip was finished. We became expert at cracking it, and it made a report every bit as good as a leather stockwhip. Unfortunately it didn’t last long as it quickly dried out, and after a few days became useless. However, there was no shortage of flax to replace it.

Fishing Some of our time was spent fishing for herrings at the mouth of the Pororari, and occasionally we did a spot of trawling for flounders. Sometimes we were lucky enough to catch a snapper on a line thrown out from a rocky platform on that part of the coastline at the rear of our farm.

Then during the season we spent many hours scooping up whitebait from the river. In those days there were not such things as registered stands, and more often than not we had the whole river to ourselves with no restrictions whatsoever. There was so much bait in the river that it was most unusual to arrive home empty handed. Sometimes the river seemed to be alive with the fish, and I remember once catching a kerosene tin full in less than half an hour. In the early season we gorged ourselves, but after two or three weeks we could not look at another fish until the following year. My younger sister seldom ate them as she could not bear their soulful eyes looking at her so sadly. Her request that their heads and tails be cut off only met with raucous laughter! There wouldn’t have been much left of the fish.

Most of the catch ended up feeding the garden. There was no commercial outlet then, as refrigeration was unknown and there was no way of keeping the bait fresh for any length of time. We used the river for swimming in quiet times, but as the current was swift, we avoided it when it was in flood. The Bullock creek provided us with good eeling.

Leslie’s memories of the girls’ games Dick’s sister, Leslie, has written about the games she and her sister used to play.

We played a lot with the Fischer children; they were all boys except Mary and Irene, and Eileen and I used to spend a lot of our time trying to keep up with the boys and Dick, who would often take to the bush. One game we had was to swing over a gully and back, clutching a supplejack vine. I only tried once; I wrapped my hanky round the vine and off I went. The hanky slipped, and I plummeted into the gully. I was very hurt, both physically and dignity-wise.

The boys came in very handy for gathering Kie-kies (giggies), which were an edible flower of exquisite flavour. They would shin up a tree, gather the giggy from its vine, throw it down and by the time they got down we had them well disposed of.

Being rather isolated we children had to devise our own games. Dick wasn’t interested in ‘girls’games’ and used to drift up to Fischers’ to join up with whatever they were planning. One of our games we called’legging’. We would have two supplejack sticks each and set off down the track, or wherever the fancy took us. We were horses, the two sticks becoming our forelegs, and in this manner we covered a lot of ground – good exercise if nothing else. We had three of four ‘legs’ all named, of course.

Another ‘horse’ game involved round tobacco tins, held upside down in our hands. Our arms were our forelegs; our own legs, with straight knees, came behind, and, backsides in the air off we went, the tins making a lovely scrunchy sound on the track. Our back views must have defied description!

There was some lovely yellow clay by the creek, and we spent hours making models, lovingly smoothing them with water and leaving them to bake in the sun. The results were anything but satisfactory.

People think of the West Coast climate as very wet, but my memories of the weather at Punakaiki are of heavy showers followed by steam rising from the ground and a fine spell. If we had finished all our jobs such as milking or turning the churn when it was wet we stayed inside. We played cards – Snap with a conventional pack of cards, and Happy Families and Rickety Kate with special packs. We played pinning the tail on the donkey, drew in our scrap books or played Pick Up Sticks, apart from cards the only bought game I remember. Books and toys were few as money was short. We had none of the entertainment valued by today’s children – no radio, television, video or computer.

Whatever material advantages we may have lacked, looking back I feel that we had a wonderful childhood with so much that was interesting to occupy us that the days were never long enough. We had no idea that our parents were struggling with poverty until after five years they told us we had to leave the farm because they had no money left. We did not go hungry, and they gave us what money could not buy – the security of loving parenting and a happy family life.

Be sure to read Growing Up in New Zealand Part 23 in which Dick describes the children’s daily life on the farm.