Part 23 – Life on a West Coast Farm in the 1920s – Difficulties and responsibilities Dick O’Callaghan – 14/09/01

We moved to the West Coast in 1922 when I was only eight. The farm was some three miles distant from the Punakaiki River and to reach it we had to cross both that river and the Pororari. Both rivers had swing bridges built across them and these were very narrow and took pedestrian traffic only. Getting supplies to the farm depended on the rivers not being in flood. Life for my parents must have been very exhausting and difficult.

Few conveniences in the house

|

|

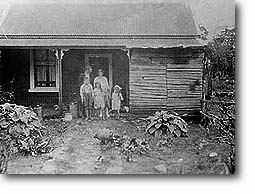

| The O’Callaghan family in front of the house where they lived for five years Photo source Leslie Walker (nee O’Callaghan) |

|

|

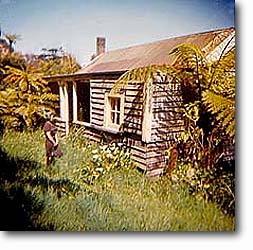

| The farm house now derelict Photo source Leslie Walker (nee O’Callaghan) |

Living conditions on the West Coast, when we moved there, were very primitive. As a child I accepted the way of life.

We had a small tank to catch the rain water from the roof, but we never used this for drinking purposes, and anyway it lasted only a few days unless rain fell at regular intervals. A hundred yards into the bush ran a small stream, and from this we filled buckets and four gallon kerosene tins in which we carried the water up to the house. This was a regular chore, and the water was of excellent quality and used for all purposes, whether for cooking, drinking, or bodily cleanliness. A copper outside the back door was used, not only to wash soiled clothing, but also to heat up water if this was needed in any great quantity. Fuel used in the copper was almost entirely wood, of which there was no lack, but which had to be gathered from the bush and cut into lengths. We used dry supplejacks for kindling.

Cooking was done on an old iron stove also fuelled by wood and sometimes coal. Water was boiled in kettles, saucepans and other containers on the top of the stove, and baking done in the oven. From that oven we enjoyed many a delicious meal, as my mother was an excellent cook. The cakes that came out of that oven were second to none, and we also baked our own bread.

Our weekly bath was taken in an oval baby bath which was just large enough to sit in with knees tucked up. The water was heated either on the stove or in the copper. It was largely a matter of standing up and sponging ourselves, always hurriedly, as others were awaiting their turn and there always seemed to be a shortage of hot water. Why this should have been I don’t know, unless the water took a long time to heat, or there was a reluctance to burn too much fuel, which, while not in short supply, took valuable time to collect from the bush.

In the living room was a huge fireplace and we seemed to be constantly pulling chairs forward or moving them back, depending upon just how fiercely the fire was burning. Toast made over the coals still seems to me to have been much more appetising than that prepared in the “pop-up” electrical toasters in modern use.

The children’s responsibilities with the milking The life was very strenuous for children of our age. As we grew older we were expected to give a hand with the milking in the morning. Then after having walked the two miles barefooted to and from school, a total of four miles, we had to set to and help again in the evening.

On the top side of the road, about a couple of hundred yards from the house, there was a huge overhanging rock with a large area of space underneath. I suppose it could almost have been called a cave, and in this area we had space for our cowbails and our separator. Outside this we had built a yard to contain the cows awaiting their turn to be milked. In wet weather the yard became a bog, and often we children were knee deep high in mud. It mattered not, as we were always barefooted anyway and it wasn’t much trouble washing legs later. My father wore gumboots, as did my mother when she came up to the yard to give assistance with the separating and other such chores. She never learned how to milk, probably because she had no desire to do so.

Many years later, when visiting the district, I had much difficulty in finding the location of the overhanging rock and cowyard. The rock seemed to have shrunk and the space beneath largely filled in. It is possible that the formation of the road had something to do with the changed topography, or that a large earthquake a few years later after our departure caused some change.

Leslie and I soon learned to milk, and either one or both of us milked four or five cows night and morning. As Eileen grew older, she also was initiated into the mysteries of the cowyard, but her memories seem mostly to be limited to squirting milk directly into a waiting cat’s mouth, and to a cow’s dirty tail making unpleasant contact with her face! She swears however, that she really did learn to milk!

After separating, the cream was carried in buckets back to the house and poured into large cans which were collected periodically and transported over the two rivers for “Boss” Mathias to take to the factory. We drank some of the skim milk, but most of it went to feed the pigs.

During winter months we milked only one or two cows and so dispensed with the use of the separator. During these months the milk was poured into large pans, and, when the cream came to the surface, it was skimmed off. We made our own butter, and I spent many an hour turning the handle of an old wooden churn. Sometimes the cream turned into the butter quite quickly, but more often than not, it seemed to take many frustrating hours of tiring work before success was achieved.

Getting to and from school We had to travel a distance of some two miles to the Punakaiki School for our education.

|

|

| The three children snapped by a touring photographer on the way to school Photo source Leslie Walker (nee O’Callaghan) |

|

|

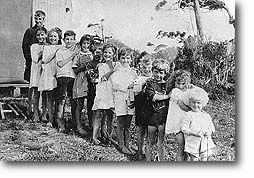

| The children of the Punakaiki School Photo source Leslie Walker (nee O’Callaghan) |

Usually we walked, always barefoot, and Eileen tied hankies round her ankles as she used to knock them together. Sometimes we were permitted to ride a horse, but we were not allowed to saddle it. So the three of us climbed aboard with the child in front taking the reins and clutching the mane of the horse for balance. The remaining two children put their arms around the waist of the child in front and off we would go. It was a bumpy ride, especially for the poor unfortunate at the rear on the rump of the animal.

Punakaiki School The school was situated immediately north of the present tearooms which were built many years later. Opposite, across the road, was the track leading to the blowholes, famous for their pancake rock formation. The school catered for all classes up to standard six, so the teacher coped with pupils of all ages. Over the years I was there the attendance ranged from nine to nineteen.

Guiding tourists to the Punakaiki Blowholes In the mid-twenties the Punakaiki blowholes did not attract visitors in today’s numbers, no doubt because of the isolation of the area, lack of transport, and little knowledge of the attraction in other parts of the country. However, there were occasions when small parties did arrive, often during the school lunch hour. Most of these visitors had no idea how to reach the blowholes, as there was then only an unmarked bush track leading to them. As we knew the area well, we often guided them along the track through the bush. Almost invariably we were rewarded with a small coin for our services, and although we were often late back to school, we always thought the recompense was well worth any reprimand we might receive from the teacher. In our opinion those blowholes were somewhat dangerous, not so much the blowholes themselves, but the surrounding area. We always took the utmost care, as it would have been very easy to slip from the rocks and fall into the hole itself. Survival would not have been at all likely in that event. Of course, since then, much has been done to improve the safety of the surround with the building of protective fences and the erection of warning notices.

Click here to read more of Dick O’Callaghan’s story.