Dorothy – 07/09/01

An interview with Elric Hooper – recently retired Director of the Court Theatre in Christchurch – Part 1

|

|

| Elric Hooper Photo source Elric Hooper |

When Elric left Christchurch Boys’ High School he studied at the University of Canterbury and there in the Drama Society he acted in Shakespeare productions directed by Ngaio Marsh.

Working under Ngaio Marsh Looking back at the experience of being in her productions Elric recalls that Ngaio taught by her wonderful example of physical energy and vocal fullness. He challenges the recent acceptance of Mervyn Thompson’s statement that Ngaio Marsh despised New Zealand speech. She is often blamed for knocking the New Zealand speech, but what she disliked was its lack of energy and fullness, its inability to express the widest range of vigour and emotion. It wasn’t the sounds she was despising, but the meanness of the sounds. She was asking for variety and the vigour of sound found in Scottish and French voices, not for orthodoxy of pronunciation. These characteristics can be heard in the voices of many actors she worked with. She wanted "a technicolour language, not a black and white one." Her own vigour and energy were the greatest advocates for that.

|

|

| Ngaio Marsh Photo courtesy of Mannering and Associates Ltd |

Being fundamentally a painter she saw things ‘in painterly terms’, and then in kinetic terms. Elric always encourages young directors to look at paintings, at the subtle arrangement of figures as on a stage. However, that is derived from the old proscenium stage, the picture stage, which he says can be a danger. The scene should be viewed sculpturally. When the Little Theatre at Canterbury College was destroyed by fire Ngaio was released from its restraints, and when working in the Great Hall she viewed her productions more sculpturally. One of the great transformations of the twentieth century theatre was away from the theatre as picture to the theatre as moving sculpture seen more three dimensionally. This led to the evolution of modern theatres where, as at The Court Theatre in Christchurch, the play is thrust into the audience who can see the air around the actors rather than the air behind the actors, creating a whole new dynamic in performance.

Elric always says to actors that the most lively space is the space between actors rather the space that the actor occupies. Ngaio used to say that backs are one of the most expressive things that the human body has, and the old adage about never turning your back upon the audience is rubbish and is derived from performance in front of royalty.

Ngaio’s methodology Elric has been greatly influenced by Ngaio’s disciplined approach to her craft. In order to save time when lighting was complex Ngaio went through every scene of the play and drew large ciricles in different colours to show the technicians where the peak points of the play were, where the movement took place. Elric has followed this practice and earned the gratitude of the technicians. He photocopies dozens of sheets of the ground plan of the theatre labelling each sheet with the act, scene, site of the action and time of day. Then he uses vectors to show the actors’ movements. He does not do this until part way through the rehearsal period so as not to restrict the actors’ evolution of the role. Ngaio most likely inherited this from the nineteenth century theatre. At that time because shows toured they had to send in advance lighting plots so that when the company arrived on a Monday morning to open on a Monday night the lighting would already be up, having been put up on the Sunday evening.

Elric believes that everybody who worked with Ngaio and later went to study elsewhere realised that the fundamental things she taught were very good, but there were a few shocks in that some of the techniques were regarded as ‘old hat’. Because Ngaio worked so much with students she had to teach technique as she went and quite often because the actors had no technique and no developed imagination she could be quite draconian about imposing on them her interpretation.

|

|

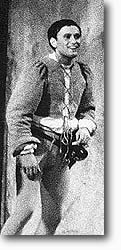

| Elric Hooper (right) as Hamlet with Jonathan Elsom (left) as Laertes |

Elric’s view is, "If actors know what they are doing and the role is clearly evolving well you leave them alone and take the credit for it!" With some of the brilliant Court actors like Stuart Devenie and Geraldine Brophy he needed only to explain the technical details of the performance and then leave them to develop the role. "A delight in working with people like that," Elric said, "is the surprises they bring to the rehearsal. Your job is really that of referee, which means that you don’t let other actors spoil what the brilliant actors are doing and you put them in the place which is best for the audience to experience it. On the other hand if actors are technically inefficient or are unimaginative you interfere like mad!

Ngaio was creating a company of actors from totally raw material and when she spotted talent she let it go."

In Ngaio’s productions Elric played the Fool in King Lear’, the Chorus in Henry V while he was studying for his Masters, and Hamlet the year after he graduated – formative experiences. In the Hamlet production Jonathan Elsom played Laertes.

From Christchurch to London to study at LAMDA Funded by a bursary from New Zealand Elric went to the London Academy of Music and Dramatic Art in 1958. He was joined the following year by Jonathan Elsom, another of Ngaio’s actors. This was a great period for that school. It was headed by Michael Macowan who was a distinguished practising West End director. He was deeply associated with what had been the Old Vic Theatre School. Just after the war Laurence Olivier and Ralph Richardson and Michel Saint-Denis, the great French director, founded a school at the Old Vic. After conflict with the head of the Board the school split up and left and many of them went to Tower House in Cromwell Road and took over LAMDA. Many of the teachers at LAMDA had come from, or been trained at, the Old Vic School. The most remarkable was Michael Macowan himself. Another wonderful teacher was Norman Ayrton who was Joan Sutherland’s coach.

Voice training Probably the most famous and influential teacher was Iris Warren who taught voice. She is the founder of one of the great modern schools of speech. and her most famous pupil is Kristin Linklater, “the goddess of the voice” in the United States.

"Iris was wonderful because she taught a seemingly liberating natural method. Two things I always remember her saying were ‘There is no such thing as technique. There is only liberty.’ By this she meant that you worked hard enough with your voice and your body so that all you had to do was think and it would work." said Elric. "Vocal teaching is far and away the weakest area of teaching in this country, in the sense that some of the schools are not exploring the total possibilities of the students. The voice is more than communication. It is an act of the imagination. It is music in the sense that it is not merely functional. It is not merely there to convey recipes. One thinks of the great voices like Gielgud, Burton or Sybil Thorndike that bring with them the burden of feeling and unforeseen emotion. When Gielgud says the great speech from Richard III on the death of Clarence you get more than your money’s worth."

One of the problems is that with the coming of the Brechtian approach in the sixties and seventies with the search for suchness and reality there was a revolution against The Voice Beautiful – and in Elric’s view rightly so. This meant the passing of the style of going on stage and delivering lines in a beautiful voice without conveying the true meaning, Like many revolutions, however, in some ways it has gone too far. Wonderful voices can get the audience or the radio listener truly excited and involved in what is being presented.

"Both Ngaio Marsh and Iris Warren were emphasising the athleticism of the voice – the sheer physicality of the voice. What is so wonderful about Mediterranean speech is it’s a weapon! Very few Italians speak Italian as if they are apologising for something. They are using it in the battle of life as a potent weapon. I suppose it’s with the tradition of English politeness which has probably pervaded here we have become more and more reticent about speech. Just walk down a street in Athens or Madrid and you think there is an altercation going on, but no, it’s a conversation about what we had for dinner last night. It’s the vigour of the speech that strikes us.

"Particularly in Renaissance plays, where the English are more like the Italians than they are now, that vigour of speech was what was both Ngaio Marsh and Iris Warren were pursuing – the excitement of the human voice, its possibilities and its range."

Engagements as an actor

|

|

| Elric as Balthasar in Romeo and Juliet |

Elric was able to support himself by supplementing his bursary by taking boring jobs in the holidays. After performing in a Shakespeare competition at LAMDA judged by Michael Benthall from the Old Vic Elric was offered a job there understudying Tom Courtney in ‘The Seagull’. His first onstage experience was in Zeffirelli’s ‘Romeo and Juliet’ playing Balthasar and understudying Romeo. This was the famous production of ‘Romeo and Juliet’ with John Stride and Judy Dench.

Elric remained with the company for two and a half years. He toured the United States and the capitals of Europe with ‘Romeo and Juliet’ and Shaw’s ‘St Joan’ where he played Dunois’s page and a monk in the trial scene.

In 1964 Elric played in a television production, Shakespeare, Man of the Year. The programme presented Shakespeare through the ages and the photo shows Elric in a group presenting a Shakespearean madrigal in the eighteenth style.

|

|

| 1964 Television Production Shakespeare, Man of the Year Left to right, Elric Hooper, Anna Pollock, Charles West, Patricia Routledge |

The next most interesting phase of his career was with Joan Littlewood’s famous Theatre Workshop. She had already done ‘Oh, What a Lovely War!’ and Elric played a role in this production in England while the company toured abroad and then played in it again when it toured the Continent.

At the Oxford Playhouse he worked with Frank Hauser and the great Greek director Minos Volonakis. With Volonakis he worked as an assistant director.

As time went on he realised that because he is a small man with a boyish appearance he was not going to make the great transformation from boy actor to leading man. As with a lot of actors like him he would go from boy actor to character roles. He believes that from the beginning he has been a character actor and that his most successful performances have been in character roles.

Singing Elric was now learning to sing properly, as he put it, with lessons from a wonderful teacher called Ernst Urbach from the Vienna State Opera. He was impressed by Elric’s intelligence and his analytical skills, and thought that although he had great instinct he often did not let go enough for his singing to flower fully. This meant that he was temperamentally a director rather than an actor.

Back in New Zealand Elric senses change in the theatre scene When Ngaio brought him back to New Zealand in 1969 to play Puck in The Midsummer Night’s Dream he suddenly saw that things were about to start to happen in New Zealand. He felt that after the post-colonial period with all the big economic changes taking place with the European Common Market New Zealand was slowly being cut adrift in the South Pacific. A new feeling was growing up, not only just national consciousness but the growth of professional theatre companies. When he was growing up the only professional company was the New Zealand players and the only way you could earn your living as an actor was through that company or through radio as radio drama was very strong at that time.

He returned to England and in 1972 came to play at the Mercury Theatre for six months. He felt that New Zealand was going to offer him the best opportunity to work as a director and use his talents to the full.

In 1975 he very sadly sold his apartment in London, packed loads of books and returned to New Zealand by sea as that allowed him to bring more luggage.

Once back in New Zealand he spent three and half years freelancing before being appointed as Director of the Court Theatre. He did a Cole Porter show and travelled with it, and worked as a director and an actor all over the country.

He started teaching because he wanted to share what he had learnt in England from people who were interesting teachers and thinkers.

Click here to read a previous article about Elric’s childhood. Click here to read An Interview With Elric – Part 2