Dorothy – 29/9/00

Choosing a site for Christchurch When Captain Thomas recommended a site for colonists to build a town in Canterbury he chose a flat area on the Plains with room for expansion in all directions rather than a site at the head of the Lyttelton Harbour where there was a comparatively small area of flat land. Given the expansion of the city over the last 150 years this was a wise decision. However given the swampy nature of the land he was choosing a site which was to present serious problems.

First Canterbury settlement The first permanent European settlers on the Canterbury Plains were two Scottish brothers, William and John Deans, and the Gebbies and Manson families who worked for them on the farm which they established at Riccarton in 1843.

The first organised settlement was in 1850 when four ships carrying British immigrants arrived in Lyttelton Harbour. The land they were to settle was on the other side of the Port Hills on the Canterbury Plains. As they stood at the top of the Bridle Path over the hills they must have felt daunted by the first sight of the Plains with extensive wetlands and raupo swamps.

Waterways The largest waterway, the Waimakariri, is a braided river. It originally flowed out through Lake Ellesmere, but has changed its course many times, and the small rivers that flow through Christchurch flow in the former beds of the Waimakariri. The main ones are the Avon, Heathcote and Styx Rivers.

In 1859 a flood in the Waimakariri River caused serious damage in the town of Kaiapoi north of Christchurch and in 1867 as a result of another flood all the low lying parts of Christchurch city were several feet under water and some houses had to be evacuated.

Drainage a problem The new settlers worked hard to establish the town of Christchurch with sound wooden buildings and a pattern of roads, but with low lying swampy areas in the central city and suburbs drainage was a major area of concern. The resources of the new settlement were inadequate to address such major work.

Health problems Because of the inadequate drainage the city had problems with flooding, foul odours and disease. Newspaper leading articles stressed the dangers of the insanitary conditions in the city. In 1874 Christchurch had the highest death rate of all New Zealand cities. After a serious epidemic of typhoid fever the local authorities had to submit to the overriding legislative power of the central Parliament.

Central Government sets up the Christchurch Drainage Board in 1875. On October 12 1875 Parliament passed the Christchurch District Drainage Act. In 1876 it passed the Public Health Act including a special clause constituting the Christchurch District Drainage Board as a Local Board of Health for the area under its control. By this time, twenty five years after it was founded, the population of the central city alone was 12,000. The need for systematic drainage of both city and suburbs was urgent. The establishment of the overriding authority ended the arguments about the responsibilities of each local authority in the area.

The preamble to the Act of Parliament stated that it was being set up ‘for the improvement of the drainage of the City of Christchurch, and the lands surrounding the said city." One of the chief means by which the drainage would be improved would be by the development of a more satisfactory means of disposing of sewage.

Ratepayers oppose building underground sewers. The first engineer to the Board, Mr Carruthers, recommended the building of underground sewers which ratepayers declared were ‘unnecessary, expensive, and dangerous to health’. They wanted to avoid the use of pumping stations and to drain the district by gravitation.

Swimming baths opened in polluted water. There was other evidence that some of the Christchurch citizens, while they expressed concern about prevalent sickness in the community, understood little about its causes. In January 1877 a swimming pool was opened in the River Avon a little upstream of the bridge which is now the Bridge of Remembrance. A deeper channel was dredged in the river between the island in the river and the bank. This meant that the baths were downstream of where the Public Hospital discharged its wastes into a stream which joined the Avon River. The drainage from the hospital was described by the Engineer of the Christchurch Drainage Board as coming "from the wash house, from the dead house, from urinals, kitchen and house washing, and from the baths." Small wonder that the patronage of the baths was not up to expectations and that people preferred to bathe upstream of the hospital.

English consultant appointed To settle the disagreements the Board employed a consultant, William Clark, an English engineer who had been in New Zealand only a short time. After a month’s work he presented to the Board a comprehensive report of seventy three clauses plus a plan and explanatory diagrams. The greatest problem he considered to be the water-logged site with water in winter in some places only a few inches below the surface or even stagnant on the surface. Surface drains would therefore be inadequate to drain the district effectively.

No sewage to be emptied into the Estuary He disagreed with Mr Carruthers’ suggestion of emptying sewage into the Sumner Estuary and stated that the sea was too far away. He therefore suggested that the sewage from the city area and close suburbs should be pumped to the sandhills in Bromley. He also recommended that storm water should be drained to the rivers.

Saturated soils create problems. He was aware that it would be difficult to complete such work in the saturated soils of Christchurch, but that the first part would be the most difficult. After that it would improve. His warnings proved to be accurate during the building of the Tuam Street pumping station as there was great difficulty because of the quicksands and beds of shingle around the site. Finally with the support of a recommendation from Mr Clark the proposal made by the Board’s engineer Mr Bell was adopted and the tank was built on a curb and lowered from the surface. The pumping station, the main sewers in the inner city and a siphon under the Avon River were completed, but the work took two years – from 1880 to 1882.

At first there were problems at the sewage farm with the drainage of the sandhills reserve, but soon the farm was working successfully and in 1890 the Colonial Analyst reported that the liquid entering the Avon and Heathcote Estuary was free of harmful constituents. Other constituents of a beneficial nature were also missing, but these were enriching the land at the farm.

Fragmentation of local controls causes problems. The Drainage Board was originally established to give an overriding control over the divided areas needing its services. The area became more divided when the boroughs of Sydenham and later St Albans were established, and town boards were set up in Woolston and Linwood. In the Drainage Board’s area there were then nine local authorities. The power of the Board to charge rates was a frequent cause of friction. Suburban and rural areas objected to paying rates much of which was spent on services for the city. The workload of the Board’s staff was consequently increasing, but the funding was inadequate.

The Board of Health and Nuisances As a Board of Health the new organisation appointed a Medical Officer and an Inspector of Nuisances. The nuisances that were reported were numerous. There were waterlogged back yards of houses where sewage was buried in holes dug in the mud. Pigs were being kept in disgusting conditions close to houses. Hospital wastes were being drained into the River Avon. There were many cesspools in the city (1000 reported in 1879) and more in the suburbs, and slops were being emptied on to peaty land. Notices were served for the abatement of 1200 nuisances in 1883 according to the medical officer’s annual report for that year.

There was a problem persuading citizens to connect with the sewers which had already been laid by the Drainage Board in some streets.

The Board of Health did valuable work for the community. In 1875 the death rate was 30.4 per 1000 persons, but by 1884 it had been reduced to 13.7 per 1000. Some of the credit was due to the improved drainage, but the unwillingness of some of the citizens to use the improved facilities means that much of the credit must go to the medical officer of the Board of Health.

Depression in the 1880s and 1890s The worldwide depression of the 1880s and 1890s increased the financial problems and forced the Board to curtail its work. It paralysed public works all over the country. The City Council even considered trying to have the Drainage Board abolished. As the financial problems continued the Board finally delegated its powers as the Local Board of Health to the local bodies within the Drainage District.

Central Government pays for the Hospital’s sewer connection. In 1884 the most important work of all, connecting the Christchurch Public Hospital with the sewer instead of letting it discharge its waste into the River Avon, was carried out and paid for by Central Government. The Government also paid for a sewer to be laid from Lower Lincoln Road as far as the Heathcote River. This enabled the Asylum at Sunnyside and the Addington Gaol to connect to the sewer.

Improvement in public health In 1889 the the death rate for the city was down to 9.77 per 1000, and the engineer stated in his annual report to the Board that this statistic made Christchurch ‘one of the healthiest cities in the colony’.

The Amendment Act 1900 allows the Board to raise loan money. This act authorised the Board to complete the sewerage system for the inner city by raising a loan which was to be repaid by a special rate levied only on rateable property in that area.

Rapid progress until the outbreak of World War I From 1901 until 1914 the number of properties connected to the sewers grew rapidly. In 1903 the districts of Linwood, St Albans and Sydenham were included in the city. The city administration had to look beyond the area within the four town belts. The Drainage Board raised a further loan in 1906 to provide sewers in the suburban areas – a task which involved building auxiliary pumping stations.

Post war expansion Little new work was done by the Board’s staff during World War I, but with servicemen returning after the war and wanting to build homes the city grew and the demand for sewerage and well drained land grew with it. When William Clark designed the sewerage system for Christchurch he expected that the city would develop like the European cities he had known and have a concentration of population over a restricted area. Christchurch spread out as most households lived on a quarter acre section with lawn and flower and vegetable gardens. This meant that there was growth in suburban areas where the system of gravity sewers would not work.

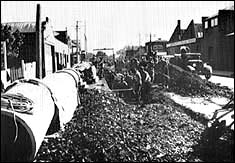

| Contractors remove a log during construction of a suburban sewer in Retreat Road Photo source Christchurch Drainage Board |

Contractors remove a log during construction of a suburban sewer in Retreat Rd in the 1920s

Photo source Christchurch Drainage Board

In 1927 the Board was at last granted the power to compel householders to connect their properties to the sewers, and also set up a system under which it could lend them money to help them to connect.

More pumping stations needed Loans were raised to finance the extra pumping stations needed to carry sewage to the farm and it was possible to run them on electric power as a power station had been built in inland Canterbury at Lake Coleridge and ensured a reliable supply of power. Fortunately such major works were completed and over 10,000 houses were connected to the sewers before the Depression of the 1930s.

| A pumping station under construction Photo source Christchurch Drainage Board |

Stormwater drainage During the 1920s though the Board’s work was largely on extensions to the sewerage system, there was also work done on stormwater drainage, deepening some of the larger and more important drains.

During the Depression the Board raised unemployment loans and relief workers cleared, deepened and widened the Heathcote River which had caused some flooding and improved the main drains in the city and suburbs.

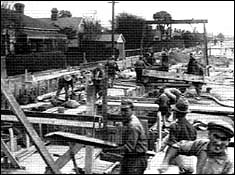

| Construction of the Durham St stormwater sewer Photo source Christchurch Drainage Board |

During the 1930s repair work was needed on the main sewer feeding the Tuam Street pumping station.

| The Board’s staff working on repairing the Tuam St sewer Photo source Christchurch Drainage Board |

| The Board’s staff working on repairing the Tuam St sewer Photo source Christchurch Drainage Board |

During the war and the immediate post-war years no new developments were possible.

Christchurch reaches its centenary. In 1950 the city founded in 1850 celebrated its centenary. It had been made in the main a pleasant and healthy place to live. As Christchurch entered its second century there were major developments to come, improving and extending still further the systems begun by the Christchurch Drainage Board seventy five years before.

For information for this article I am largely indebted to two books:

Agnes I Hercus, A City built upon a Swamp , Christchurch, 1948, Christchurch Drainage Board

John Wilson, Christchurch: Swamp to City: A History of the Christchurch Drainage Board 1875-1989, 1989, Te Waihora Press for the Christchurch Drainage Board.

Permission to use photographs credited to the former Christchurch Drainage Board has been granted by the Christchurch City Council.