Life in the Public Works Camps on the Kaikoura Coast in the 1930s

Dorothy – 14/12/01

This article is based on an interview with Leslie Walker (nee O’Callaghan) supplemented with information drawn from the stories published in Public Works Camps: Poor Kids’ Paradise compiled by Pauline Blincoe.

During the Depression of the 1930s many men lost their jobs and were grateful to accept work on Public Works Department projects. They were paid a pittance for manual labour which was a difficult adjustment for men who had been employed in professions or skilled trades. They were provided with free but fairly primitive housing. There were twenty six of these camps, but in this article the information relates to those on the Kaikoura Coast.

Pauline Blincoe recognised the importance of recording recollections of life in the camps while it was still possible to contact a number of the people who had lived there.

Life for the men For most of the men the work on building the railway (now known as the Coastal Pacific Railway) was tough physical work done with pick and shovel, but they preferred it to being jobless. The good community spirit made their lot more acceptable, and everyone was in a similar situation of trying to make ends meet with very little money.

Hard work did not stop when they came home to the camp as most of them developed vegetable gardens to help feed their families, and chopping wood for the stove and copper was a regular chore.

Life for the women Living in a hut with limited space and none of the conveniences that ease the lot of the housekeeper today meant a lot of hard work.

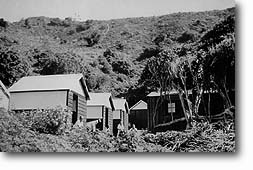

Family houses The family houses consisted of three rooms with the kitchen in the middle and a small bedroom at each end with a total area of about 350 square feet. If a family had more than three children an extra hut was provided outside.

Leslie recalls that the houses where she lived were built of wood and lined with Sisalcraft – tarred paper. In the kitchen there was a small coal range and there was a cold water tap outside the back door. Des Walker was working near Goose Bay so the family lived in the Goose Bay Camp – one of the smaller settlements. There was no electric power, so the house was lit by Aladdin kerosene lamps with a methylated spirits wick, or by candles. Ironing was done with a Mrs Potts iron heated on the stove.

In the larger camps there was a diesel generator which gave power until about 9 p.m. This meant that there was electric light in the kitchen, but no power point for a radio.

Washing Each family house also had a tin shed with a copper for washing and heating water and a tin bath. Many women made their own soap and took a pride in hanging out a white wash. Leslie commented that to have a white wash was very difficult as the roads were not sealed and dust blew everywhere, including on to the washing. She lit the copper once a week, but did washing in a basin on a bench outside on other days as Des’s working clothes got very dirty. A clothes line was rigged up with props to support it. Des organised a rack with a pulley so that the washing hung under the roof and dried with the heat from the stove.

One person’s reminiscences in Pauline’s book included her mother’s saying;

- It’s no disgrace to be poor. It is a disgrace to be dirty.

Toilets For each family there was a toilet a short distance from the back of the house, and the contents of the bucket were collected once a week by the nightman and all the sewage was emptied into the sea. Cut up newspapers or the tissue papers wrapped around apples served as toilet paper.

For nervous children going to the toilet had the usual problems of non-flush toilets – blowflies, spiders, and even wetas, and possums on the roof.

|

|

| After the storm |

The southerly and nor’west wind storms on the Kaikoura Coast can be very severe, so the houses were wired to the ground, but even then there was considerable storm damage.

Leslie recalls a storm in which all the toilets except theirs were blown over. After that those that had blown over were wired to the ground, and in the next storm they remained in place, but the Walkers’ toilet was blown over!!

Furniture Most families had only basic furniture – a wooden table and chairs, perhaps a dresser, one or two armchairs for the parents to use, and beds, often shared by the children. Wardrobes were devised by hanging a curtain across a corner of the room. Apple boxes served as containers for clothes. Most people had few clothes or possessions so storage was not a problem.

|

|

| Single men’s quarters |

Single men’s quarters Each man had a little hut with one small window, shelves, a little table, a bed with a straw mattress and a Queen Bee stove. Many of the huts had wooden sides part way up and the upper part was made of canvas.

Food The store in the larger camps sold groceries, the baker brought bread twice a week, a truck called with fruit and vegetables for sale, and the butcher called bringing sausages galore and in one camp giving each child a saveloy. The Goose Bay camp had a Post Office, and a grocer from Oaro brought groceries and fruit and vegetables. They collected their milk from a nearby farm. Pushing a pram over the unsealed roads and carrying a billy of milk was quite an adventure.

More than one person recalls going mushrooming, picking fuchsia berries in the bush for making jam, and finding cape gooseberries by the beach. Wild pigs, crayfish and paua were plentiful and used to supplement the food supply. Some of the men at Goose Bay would go out fishing in a dinghy and catch enough terakihi to give to everyone.

Having a bath For most families Saturday night was bath night and water was heated in the copper or on the stove and poured into a tin bath. Several of the family had to use the same bath water. One person recalls another form of Saturday cleansing – a dose of castor oil or medicine made from senna leaves, or liquorice powder.

Leslie and Des and the family had a small bath each night using hot water heated on the stove, and indulged in the luxury of the bigger tin bath with water from the copper only on Saturday nights. They felt that the work on the railway meant that some sort of daily bath was essential.

Clothes Clothes were regularly re-cycled and mended to give them the longest possible life. One woman took sewing orders and did all the work by hand until she had saved enough to buy a treadle Singer sewing machine which was greatly treasured and gave her the chance to earn more money.

Life for the children The articles in Pauline’s book give a detailed picture of the children’s lives. It is interesting that in their reminiscences they remember their years in the camp as a wonderful time. There is no talk of the hardship resulting from real poverty. In their reminiscences there is little reference to cold days and heavy rain and nothing about feeling bored staying indoors, as one might expect from modern children. Icy mornings meant the fun of crushing the ice on the puddles and throwing it at each other.

Leslie remembers how friendly and supportive the women were to each other. The children regarded the people in the camp as one big family and addressed the adults who were friends as Auntie and Uncle.

School Schooldays are recalled with affection, no doubt because of the quality of the teaching staff. There is frequent mention of the head teacher at Aniseed, Les Brown, who is described as a caring teacher who was determined that the children’s individuality should be developed. He taught them to appreciate their natural environment and to recognise plants, trees, insects and birds. Growing around them were matai, totara and rimu trees, home to native pigeons, tui, bellbirds, and fantails. Mr Brown had taught at Tolaga Bay and was able to teach his pupils Maori songs, chants, poi dances and a haka.

|

|

| Bert O’Brien, Pem Chatterton and Basil Simmons in uniform just before leaving to serve overseas |

|

|

| On a hiking trip 1939 |

The assistant teachers, Pem Chatterton, Basil Simmons and Bert O’Brien, are remembered as making classes very interesting.

When news came through of the death of Bert O’Brien on his first day on active service all the people in the camp grieved deeply about the loss of such a vital and caring person.

Pem Chatterton initiated Sunday rambles and under his leadership large numbers of children explored the Kaikoura Coast on what they regarded as memorable outings.

Many of the children had a long walk to the school. Most went barefoot, and some suffered chilblains. Shoes were a luxury that most families could not afford for their children.

Entertaining themselves using available resources Like Dick and Leslie O’Callaghan in the article about life at Punakaiki, the children seemed to have wonderful skills at devising entertainment for themselves. In the camps they fashioned canoes from spare corrugated iron and play in the nearby stream.

They built huts from tin and sacking.

Butchers’ skewers were turned into knitting needles. They devised sledges to use on grassy slopes. They played on the beach with old tyres. They explored the rock pools. They swung across creeks on supplejack vines.

|

|

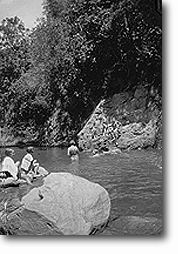

| Swimming pool |

The beaches along the Kaikoura coast are not suitable for swimming. The men in the Aniseed camp used cement bags filled with gravel to build a swimming hole in the stream and the children spent many hours there in the summer.

Community life The store which supplied groceries and a wide range of other necessities was the centre for the camp, and when the service cars called people would congregate to collect their mail and newspaper.

At the large Aniseed camp the YMCA building, built of unpainted corrugated iron, was the centre for social events. The building has been described as being large enough for dances, showing films, and putting on concerts. There was a supper room and a good stage and the dressing rooms were adequate. People gathered there to play billiards and table tennis.

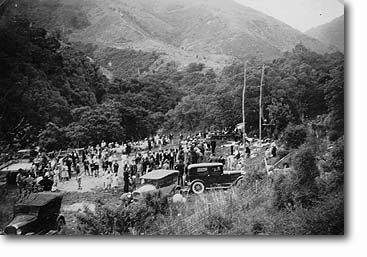

The social events which were organised usually involved the whole family. Sports days and camp picnics were gala days.

|

|

| Gala Day |

The camp dances were very popular and attended by people from other camps. At Aniseed the school headmaster, Les Brown, was a good pianist and provided the music for the dancing.

Movies were brought to the camp and shown in the YMCA building. While the reels were being changed everyone would join in a sing song.

Camp concerts were greatly enjoyed, especially by the children. They involved most people. Les Brown and the other teachers in the Aniseed School would write plays and songs and the children loved these occasions.

Mr Worthington, the drama tutor for the Workers Education Institute in Christchurch, travelled to country districts and would help with play production.

At some camps the men cleared away the bush and created a sports ground. Some camps had tennis courts and tennis was popular among the adults and the children.

None of these activities were available at Goose Bay, but Leslie said that as the mother of young daughters she was too busy to feel the lack of social life. In addition to keeping house for her family she cooked breakfast and dinner for two men living in the single men’s huts. Payment for this helped to eke out the low wages.

There was no ACC, but when anyone had an accident the other families offered support during periods when the man of the family could not work on the railway, or the mother was too unwell to care for the family.

Having babies Leslie had two daughters while they were living in the camp. Once labour pains started someone with a car would take the woman to Kaikoura Hospital travelling over what were then very rough unsealed roads.

The years of World War 2 Blackouts were strictly enforced in the camps, and regarded as of particular importance as they were sited on the coast and the lights could have been seen by enemy shipping.

Families cultivated Victory Gardens to increase the food supply, children knitted peggy squares, and women knitted balaclavas and socks for the men in the forces. Children also collected ergot which was believed to help in the healing of wounds.

Transport during the war Petrol was severely rationed and some families had cars powered by a gas converter so they had some flexibility about travel.

Keeping up with the news Car-battery-powered radios gave some families the chance to hear the news broadcasts and the saddening lists of casualties. Newspapers could be bought at the store each day. As there was no television the children were protected from much of the distressing news during the war.

The time when the family shared in an entertaining programme was when they gathered to listen to “Dad and Dave from Snake Gully”, a popular Australian serial.

Looking back Remembering her years in the camp Leslie recalls the spirit of acceptance among the people living there. No one complained. They settled down to a very hard-working way of life for both men and women.

“I was happy,” Leslie said, “and I made friends. I still see them after over sixty years. The only one of my daughters who was old enough to remember our time there looks back on it as a happy time and after reading in Pauline’s book about the education the children received she regrets that she did not have her schooldays there.”

Pem Chatterton took the photographs reproduced in this article. We thank him for giving us permission to use them. Alert as ever he wrote me an interesting letter in copperplate handwriting.

Copies of Public Works Camps: Poor Kid’s Paradise may be purchased from

Mrs Pauline Blincoe 1212 Main Road Pakawau RD1 Collingwood 7171

Pauline has compiled another book, Yesterdays of Golden Bay – glimpses of past industries and PWD camps.

Price of each book $50.00 plus $1.40 postage