Dorothy – 28/8/98

Honorary Curator of Ethnographic Textiles and the Maori material in the Otago Museum. If you haven’t already, read last week’s article on the Otago Museum.

|

|

| Margery Blackman |

Margery Blackman first became known nationally in New Zealand as a tapestry weaver, but more recently she has turned her energies to curatorial and conservation work with historical textiles in Dunedin public collections.

Margery’s intense interest in textiles began when she was a student at the Home Science School at the University of Otago.

Research and self-generated learning Weaving Her weaving began when she was living in Scotland in the 1960s. Being unable to find suitable tuition in weaving she studied books and was largely self taught.

Interest in historical textiles At about the same time her interest in historical textiles began. She took advantage of seeing museum displays in Britain and this gradually extended into building up a worthwhile personal library on the history of textiles throughout many cultures.

Honorary curator at the Otago Museum Margery explained, “As there is no tuition available in New Zealand in this specialised area the learning was inevitably self-generated. Overseas travel added considerably to my knowledge as I was able to study museum collections, attend occasional lectures and conferences. This led to my being invited to be the Honorary Curator of Ethnographic Textiles and Costume from Other Cultures as well as the Maori material in the Otago Museum.”

This meant identifying, researching and caring for the Maori cloaks and other textiles, such as mats, bags, and some basketry, and the Otago Museum collections of material from Asia, including China, India, Indonesia, and Japan, from Africa, the Middle East and North and South America, and folk costume from the Balkans. Apart from the Maori material the major overseas collection is from China.

Recent academic acknowledgement of the study of textiles Margery finds it surprising that it is only in the last twenty or thirty years that academic disciplines have included the study of textiles and costume which are so much a part of the every day life and the ceremonial of a people.

Coptic collection of interesting origin One of the small, but rare, collections in the museum which has especially interested Margery is fragments of Coptic and early Islamic textile fabrics from archaeological sites in Egypt. They were given to the museum in 1946 by a Greek antique dealer, a Mr Tano, who had an antique shop in Cairo. He gave them as a tribute to the performance and courage of the New Zealand Second Expeditionary Force in Greece and Crete in 1941.

A museum benefactor, Colonel Waite, collected a lot of stone, pottery and other artefacts from the Middle East for the Otago Museum during his overseas service in both World Wars. He was at Gallipoli in World War I and served in Egypt as a welfare office in Egypt in World War 2.

Mr. Tano knew Colonel Waite and would probably be aware that the other artefacts going to the museum did not include textiles. He selected seventy pieces extending from the Coptic period about 400 to 500 AD through the early Islamic period up to imported Indian printed fabrics up to about the eighteenth century. These are all fragments. Mr. Tano clearly recognised the importance of such textiles being represented in a museum and sent this collection to the Otago Museum.

Three fragments are currently on display in the museum. A larger group has been displayed at the Dunedin Art Gallery and the National Library Gallery in Wellington.

The fragments are part of garments which were found in burial grounds and rubbish dumps, and which survived because of the dry climate. When the excavations began in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries the decorated parts were all that was rescued from the deteriorating garment so they became separated from the original setting.

Several fragments feature lions. The Copts were the early Christians in Egypt, and the lions are thought to represent the lion of St Mark who was reputed to have taken Christianity to Alexandria. A fragment from a few hundred years later is decorated with grapes and a simplified form of grape leaves. Some of the fragments were parts of long bands that were parts of otherwise plain linen garments. These bands featured saints and other religious symbols.

In the Islamic period there is Arabic lettering on the garments. Margery has had some of them translated, and they quote short phrases from the Koran.

Study of Maori cloaks Because she is a New Zealander and because Maori cloaks are unique to New Zealand Margery felt that it would be wise to become familiar initially with some of the material in the Otago Museum. Then because she was fortunate enough to travel when her husband had sabbatical leave, over a ten year period she collected a lot of information about cloak collections world wide. Collections are held in London, Oxford, and Cambridge, in Scotland and some are in Switzerland, Italy, France and Germany. She travelled to Sweden to see a cloak which was collected on Captain Cook’s first voyage to New Zealand. She has also seen cloaks in several North American museums and a few in Australian museums. This means that they are fairly widely spread.

Structure of the cloaks What has interested Margery in particular has been the fine details of the structure – the way that the threads are manipulated together. They are made of New Zealand flax, phormium tenax , from the fibres extracted from the leaves. Many were decorated with feathers for prestige cloaks, or tags of flax leaf for rain cloaks forming a thatch-like structure. Margery’s particular study has been of the finely twined decorative borders known as taniko, a technique which appears to be unique to the Maori.

Clothes of the Pre-European Maori At this point I asked Margery how the early Maori people kept warm in the winter. Her reply was that it was a case of survival of the fittest, but that in the south there are stories of seal skin being made into cloaks, though none are known to be in existence. The skin of the Polynesian dog which the Maori had brought with them was also made into cloaks. There were never profuse numbers of these dogs, however. The dog skin cloaks were made of the phormium tenax fibre and then decorated with strips of dog skin which would give them added warmth. These cloaks were only worn by tribal leaders.

The New Zealand flax fibre with washing and beating processes to a very soft flexible fibre, so cloaks wrapped around the body would give considerable warmth. In wet or snowy weather they would have an extra outer cloak or a rain cloak with its thatch made in such a way that the rain would run off.

Sandals were worn, and sometimes a legging covering the shins, when going through the matagouri for instance. The life expectancy of the Maori at that time was probably between thirty and thirty five.

It is difficult to know just exactly what was worn by early Maori settlers as archaeologists have found so few examples of early Maori textiles in New Zealand. What is known is that there were very sophisticated, highly skilled cloak makers working at the time of European contact.

Reference books on Maori clothing There are a few good publications about Maori clothing. One of the best, “The Evolution of Maori Clothing”, was written early in this century by the great Maori scholar, Sir Peter Buck, and published by the Polynesian Society.

Another is S. M. Mead’s “Traditional Maori Clothing” published in 1969 by A. H. and A. W. Reed.

A fine more recent publication on Auckland Museum’s collection by Mick Pendergrast – “Te Aho Tapu. the Sacred Thread” 1987, is more readily available.

Other work Margery’s work has not been limited to her role at the Otago Museum. She catalogued and conserved the textiles at Olveston, the well-known historic house in Dunedin, has worked as an occasional voluntary conservator for the Otago Settlers’ Museum, and at times worked as a consultant at the Dunedin Public Art Gallery. This work has included cataloguing the lace collection at the Art Gallery and some work on the oriental rug catalogue.

Private conservation contracts As a consultant textile conservator she has undertaken a number of private contracts. Among many people in the community there is an increasing interest in old textiles passed down through the family. Private clients have asked for her advice on the care of samplers and of textiles brought back by grandfathers or great grandfathers from the First World War from places like France and Egypt. She frequently talks to groups on the history and care of textiles.

Waitaki Boys’ High School Hall of Memories Her largest contract was for the preservation of fifty three flags and eight pennants in the Waitaki Boys’ High School Hall of Memories. This task involved cleaning and repairing the flags and pennants, and strengthening those fit to be hung in the hall again. The most fragile were cleaned but not repaired and are stored as a historical record at the Oamaru Museum. Many were from former British colonies. As a voluntary extra service Margery has researched the history of the flags and pennants.

Weaving As a weaver Margery has had her work exhibited through New Zealand. Her works have been purchased by museums and galleries. She has also accepted some private commissions, including woven panels for the Dunedin Hospital and the Dunedin Teachers College.

|

|

| “Otago Banners” 1986 at Dunedin Hospital |

|

|

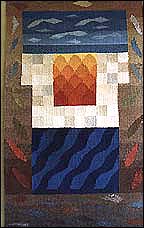

| “Origins I” 1986 at Dunedin Teachers College |

Textile exhibitions Margery has organised many textile exhibitions, including twelve at the Otago Museum. These included ‘Islamic Rugs’ in 1975, ‘Indonesian Weaving’ in 1981, ‘Treasures from Maori Women’ in 1989, and most recently ‘From Emperor’s Court to Village Festival’ – an exhibition of Chinese costumes and other textiles held in the Otago Museum. She has also written catalogues with high quality illustrations for the Indonesian and Chinese exhibitions.

The Chinese exhibition is the subject of this NZine article.