Dorothy – 16/6/00

|

|

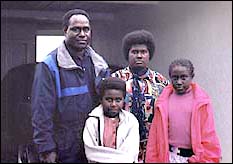

| Left to right, Sam, Josie, and Melanie, in front Imelda |

The Kauona Sirivi family in the photo are from Bougainville. At present they are living in Palmerston North in the North Island of New Zealand.

Sam Kauona Sirivi has been given a scholarship by the New Zealand Government to study to become a helicopter pilot. His plan is to return to his homeland to work as a pilot and teach others to fly helicopters, a valuable mode of transport on such a mountainous island.

Josephine Sirivi Kauona is studying computer skills and will work to improve the communication between people on Bougainville and the outside world. In 1997 she founded Bougainville Women for Peace and Freedom and became its first president.

Melanie and Imelda, Sam and Josie’s daughters, have been attending school in Palmerston North for the past year.

Their life over the last ten years has been filled with suffering and struggles – struggling for the rights of the Bougainvillean people and struggling to stay alive.

Foreign nations’ activities on Bougainville After the Spanish explorer Captain Alvara de Mendana first visited the Solomon Islands in 1568 he made a return visit in 1594 to seek for gold and other valuable resources, but became ill and died there.

The next Western visitor was the French sailor, Captain Louis de Bougainville who named the big island after himself.

Some thirty years later the British, German, Dutch and French imperialists began to establish colonies around the Asia-Pacific rim.

In the nineteenth century many Bougainvilleans were taken by Australian slave traders to work in the sugar plantations in Queensland or the coconut plantations in Fiji and Samoa.

In 1884 representatives of the German Imperial Government visited the area and offered the protection of the Reich to anyone working there. Later they used gunboats to extend their control and parts of the Solomons Archipelago, including Bougainville, were controlled by the Germans while the rest came under Britain.

Huge coconut plantations were developed along the eastern seaboard on land belonging to the people of Bougainville. Today these plantations are controlled by Australian multinational corporations. The Germans trained the natives only to support their industries.

In 1918 when Germany was defeated in World War 1 and lost her territories in the Pacific Bougainville became a Mandated Territory under the League of Nations administered by Australia on behalf of Britain along with Papua New Guinea (PNG). The people of Bougainville are culturally and ethnically related to the Solomon Islanders, but not to the people of PNG. The people of Bougainville were unhappy about this ‘political marriage’, but were not consulted.

During World War 2 Bougainville was occupied by the Japanese army. When the Americans landed on the island there was fierce fighting, and hundreds of Bougainvilleans, who were not actively involved in the conflict, were killed. Again after WW2 Bougainville was linked to PNG under Australian administration.

The people of Bougainville began their own enterprises growing cash crops undertaking very tough physical work and became a successful agricultural exporter. Highly educated people were attracted to the island and a unique village-based education system was developed. Land and hard work were the sources of the island’s wealth.

Bougainville Copper Ltd (BCL) From 1929 Australian prospectors were given virtually unlimited licences by the Australian Bureau of Mineral Resources. Land owners were seldom informed and never consulted before they worked on their land. In 1965 a rich copper deposit was drilled and a company set up to mine for copper.

This company was founded by CRA, a subsidiary of Conzinc Rio Tinto, a huge mining company. They allowed CRA to own 53% of BCL and the PNG Government 20%. How much did they allocate to the people whose land contained the copper? Nothing.

The villagers were fearful of activities that they did not understand, and afraid that they would lose their land and the mountains in which their protective tribal spirits lived.

The Australian Government saw the mine as one way of increasing the small revenue of PNG.

English and Australian mining legislation gave the company an unlimited run of the area up to 10,000 square miles around the deposit – in effect all the resources on Bougainville. With the landowners there was no agreement.

Next CRA wanted a port and when the people resisted armed police used batons and tear gas. The women threw themselves in front of the bulldozers, ready to die for their land.

In a court case in the Australian High Court the Bougainvilleans claimed ownership of the land and the copper as no compensation had been paid. The Australian Constitution states that ‘there can be no acquisition of a person’s property except on the condition that just terms of compensation were payable.’ In August 1969 the seven judges decided in favour of Australia saying that "the terms which applied to the taking of land in Australian States did not have to be applied to the Territory of Papua New Guinea". The landowners had to accept an agreement with CRA.

After seventeen years of attempts to negotiate with CRA and the PNG Government for better terms and for environmental control the Panguna Landowners Association decided that they had no other alternative. They had to mobilise.

An interview with Sam Kauona Sam and Josie come from Navuia, a village in central Bougainville. This is three hours drive from where the copper mine was developed, so they were not directly affected by the mine, but they identified with the feelings of those whose lives were changed by the mine.

Sam’s view of the past Sam talked about the political history of Bougainville. "It goes back to before Papua New Guinea (PNG) achieved its independence. Bougainville made its unilateral declaration of independence on 1 September 1975, over two weeks before PNG declared its independence on 16 September 1975. Our fathers said, ‘We are Solomon Islanders. Our ethnic affiliation is to Solomon Islanders and we have our relatives in the Solomon Islands."

"At that time Australia had a United Nations mandate to look after Bougainville. Australia was also helping and grooming PNG to become independent by 1975. The people of Bougainville made it known clearly to the United Nations representative who visited our island in 1964 that they did not want to become part of PNG. ‘We want to be on our own or with the rest of our Solomon Islanders.’ There was a petition by our people given to the United Nations representative letting them know that Bougainvilleans wanted to be on their own." However the United Nations, on the advice of the Australian Government and the rest of the world took no notice of the Bougainvilleans’ wishes.

"People put up a fight against the Government and the company, for reasons that were political, economic, environmental and social. We were in a situation of hopelessness. Multinational corporations were taking all the resources from our island and putting back nothing. That is why the Bougainville people said, ‘This is enough’. They needed to get the company, the Papua New Guineans and the Government out of their island so that they could be on their own. This was the only option left for Bougainvilleans to save their island from being torn apart by multi-national corporations".

In 1975 Papua New Guinea set up a provisional government but promised that it was for only two years.

In 1975 the people had protested to the PNG Government against a company mining for minerals on the island. The original mining agreement between the mining company, PNG Government and Bougainville Provincial Government was to be reviewed after seven years. When that review did not take place there was deeply felt frustration.

By the late eighties there was a strong sense of social and economic injustice done to the people of Bougainville. More and more land was being claimed by the company and destroyed by the mining. The environmental destruction of the island was unbelievable. For this reason the landowners demanded compensation, but the Government refused. The company refused to address issues saying that it was the job of the PNG Government.

Environmental impact of the mine The mining completely destroyed the Java river system, one of the biggest in Bougainville. That river as it flowed right from the centre of the island carried tons and tons of what the company called tailings, waste earth including deadly cyanide chemical, to the western coast of the island. The fertile flat land located on the lower plains below the mine area was completely destroyed by the tailings.

"When the mine was in operation you could not see that river," Sam said. "It was turned into mud or slurry flowing down and covered hectares and hectares of land down in the valley as it flowed to the sea. It polluted not only the land, but also the sea and air. Pollution was evident in the sea as a lot of fish and marine life was fast being destroyed. Air pollution was suspected as birds, especially flying foxes, were dying in thousands".

Read Part Two to see how the landowners were provoked into action.