Dorothy – 25/2/00

Be sure to include a visit to the observatory in your Te Anau – Milford itinerary

Have you ever

- looked at beautiful photographs or documentaries showing underwater life and wished it were possible to see it yourself?

- felt dissatisfied because an aquarium can show you sea creatures only in an artificial environment?

- envied those who have had the chance to dive and see the wonders of underwater life for themselves?

Forget those unsatisfied dreams. Visit the Milford Deep Underwater Observatory in Milford Sound.

|

|

| Milford Deep Underwater Observatory |

The brochure for the Observatory immediately caught my interest. An intriguing photo taken by a diver shows two people looking out of a window

at the underwater life in all its richness of colur and diversity. The simple wording avoids the hype and extravagant language advertisers use for

less significant tourist attractions.

It reads, “Learn about the marine life of the Piopiotahi Marine Reserve from the interesting interpretation displays. Then descend to the viewing

chamber nine metres below the waterline. Observe intimately and undisturbed, the corals, anemones, sponges and fish species within their natural habitat. This underwater community is vibrant and everchanging.”

I quote, because I couldn’t express it better or more concisely. I have praised the brochure for its restraint, but I find myself driven to superlatives in describing the experience of visiting the observatory.

Why choose to build an underwater observatory in Harrison Cove in Milford Sound? In the fiords of Fiordland there are many species which are either rare or

usually live in much deeper water elsewhere. Black coral fits both these

criteria, as it is rare and if found is usually at forty five metre depths

or more.

The Piopiotahi Marine Reserve This reserve has been formed on the northern side of Milford Sound to preserve the special underwater environment. It extends from Dale Point at

the outer end of the Sound to the Bowen Falls and along the end of the runway. All of Milford Sound is closed to commercial fishing, and no interference at all is allowed in the marine reserve half. Milford Deep Underwater Observatory is in the middle of this reserve.

Why are deep sea creatures found in shallow water in the fiords? Milford Sound was formed by glaciers. The entrance is narrow and because of

the debris which the glaciers pushed forward during the Ice Ages that entrance is also shallow. The result is that the water is comparatively

calm and gives a stable environment for the underwater creatures.

A further reason is that Milford Sound receives large quantities of fresh

water from the high rainfall and the rivers that flow into it. That fresh

water does not flow out to sea quickly because of the narrow, shallow entrance. Being less dense than salt water it lies as a layer on top of the salt water. The rain water that flows into the sound has come from forested mountains and has been discoloured by the tannins in the litter and growth on the forest floor. This results in a layer of dark water

which covers the sea water and darkens the environment below. This layer

varies from one metre to ten metres deep in the fiord, and below it sea creatures can live in a dark environment such as would be found in most other places only at 45 metres depth.

Report of the New Zealand Oceanographic Institute After the New Zealand Oceanographic Institute visited Milford Sound in 1978

and reported on the unique life under the surface laws were passed in 1980

to protect black coral and red coral which are valuable and sought after for use in jewellery.

The marine biologist, Dr Joyce Richardson, was part of the NZOI team and had obtained a grant from the National Geographic to investigate black coral.

The current manager of Milford Deep Underwater Observatory, Alistair Child,

then a cray fisherman familiar with black coral sites, dived with the NZOI

team.

The report of the research team led to the first tentative plans for the Underwater Observatory. Dr Richardson had seen the Queenstown Underwater

Observatory designed by her cousin Arthur Tyndall, and approached him about

the idea of establishing an underwater observatory in Milford Sound.

Arthur Tyndall’s firm undertook the development of the observatory which

was a combined research and tourism project. He learned to dive as it was

essential to see what was happening under the water. Considerable experimentation was done with boxes of plants and animals growing under water at the proposed site for four years before the observatory opened.

Choosing the site Harrison Cove was chosen as the site because it fitted the criteria for the

observatory:

- it is sheltered from the day breeze blowing onshore – necessary for berthing boats and taking passengers on to the observatory.

- there is minimal risk of a tree avalanche in which occasionally the trees growing on a steep mountainside in minimal soil are dislodged in a storm. (This was confirmed by the existence of a 4.5 metre black coral tree growing at 18 metres below the surface at the site.)

- the slope of the fiord below water level allowed for the observatory to stay close to the side as it rose and fell with the tide.

- it is an area which nurtures a cross section of the marine life in the Sound.

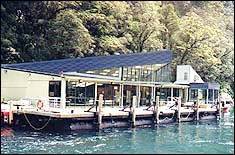

Building the Observatory A complex structure was planned. A viewing chamber with the reception area

attached was to be held to the wall of the fiord by three hinged arms, and

be able to rise and fall with the tide. Two docking platforms and a generator shed to house two LPG fuelled generators to provide power were to

be outside the reception area.

The planning was a long and detailed process. There was no room for errors

in such an undertaking.

Gaining consents and permits under the Resource Management Act required twenty seven consent processes.

If you’ve read the article on the road to Milford you will already be aware

of how difficult it is to bring in any large structures by land. The solution was to build the reception area, the docking and the generator platforms at Deepwater Basin in Milford Sound and the viewing chamber in Invercargill.

The viewing chamber was built in three sections which were taken by road to

the port of Bluff and connected. The total structure was built of fifty tonnes of steel and was more than twelve metres high and nearly nine metres

in diameter. Taking it through the Homer Tunnel was an impossibility, so

it had to come by sea for 380 kilometres through waters which were subject

to gales and along a coast which is rugged and inhospitable.

|

|

| The completed viewing chamber just before launching at Bluff Photo source Ian Hamilton |

With the windows protected and extra concrete poured in to make it stable

the viewing chamber was towed from Bluff when the weather forecast looked

favourable and reached Harrison Cove on 19 September, 1995 – a four day trip in good weather just before severe gales hit the area.

One worry was that there would be damage from semi-submerged containers. There had been news on the radio that a container ship had lost a container

in Foveaux Strait. There was a light on top of the observatory which would

go on if the viewing chamber took in any serious quantity of water. It didn’t go on. The only real problem occurred when the tow boat turned at

right angles to enter the Sound. The tow rope slackened and dropped to the

bottom and became snagged on a rock. Fortunately careful manoeuvring set

it free and the towing continued.

The planners were scrupulous about ensuring that no foreign marine organisms or other pollutants were brought into Milford Sound by the viewing chamber, so all its underwater surfaces were scrubbed down on leaving the Bluff Harbour and again at Anita Bay at the entrance to Milford

Sound.

After long hours finishing the project for the next two and half months the

observatory was opened on 6 December 1995. People from the Ngai Tahu tribe

over many centuries visited the Milford area so it was fitting that a party

from this tribe gave a Maori blessing at the opening. The heavens gave a

blessing too as the heavy rain ceased briefly and the sun shone through between the clouds.

Visiting Milford Deep Underwater Observatory Your launch trip gives you a thirty minute visit. Disembarking is easy and no time is lost. The programme for the visit begins with a short talk

about the fiords and the marine environment. The reception area features

displays and a news board noting recent special events in the underwater environment.

Information sheets are given out and you can choose among five languages.

Next comes the descent into the well of the building – the equivalent of going down three storeys.

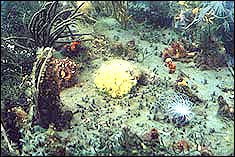

The view from the windows I was immediately fascinated by the views out of the window – first in the

dim natural light of the fiord, and then with low level lighting switched

on. Our guide explains that sunlight is filtered as it penetrates the water causing colours to be absorbed, but low-powered lights close to the

subject give the true colours of marine life. And those vivid colours give

a brilliant picture of the marine life outside.

|

| Black coral tree with snake brittlestar, hydroid fan and sponges Click here for a larger version |

|

| Red coral fan, horse mussels and sea squirts Click here for a larger version |

|

| Yellow zoanthids and a rare albino tube anemone Click here for a larger version |

|

| Cup sponges, kelp and velvet weed Click here for a larger version |

The Ledges The observatory is surrounded by ledges like a continuous series of window

boxes containing sediments and marine life native to the sound. These are

built so that they can be lowered at night and raised for viewing. They are

also lowered during storms or when divers go down to clean the windows. Hydrometers outside the windows check any drops in salinity. If it is too

low the ledges are dropped to the saline level as many of the species present are intolerant of fresh water.

Does the presence of the observers inside the viewing chamber change the

pattern of life outside? The presence of the observers creates no disturbance for the sea creatures,

whereas at the approach of a diver some take defensive actions. This means

that within the viewing chamber we see a genuine undisturbed picture of life below the water.

Important purchase Before you leave the observatory be sure to buy a copy of Ian Hamilton’s book, Milford Deep: The Story of the Milford Sound Underwater Observatory. This clearly written description of the development of

the observatory and the marine life that can be viewed there helped me to

retain clearer memories of this memorable half hour and is a useful reference book to keep.

Return to our boat The half hour has passed all too quickly and regretfully we board our boat

and return to Freshwater Basin enriched by a unique experience and loaded

with photographs to be developed.

Awards of excellence The Association of Consulting Engineers of New Zealand presented a Gold Award of Excellence to Arthur Tyndall and Noel Hanham in recognition of an

outstanding project in 1997.

In the same year the Institution of Professional Engineers of New Zealand

presented an Engineering Excellence Awards Structural to this consulting firm for the same project.