Dorothy – 19/11/99

Heated discussion and opposition from primary teachers have followed recent

Government plans to introduce national tests for children in all primary

schools so that their progress can be measured against that of their peers.

The present system of national testing Since 1995 tests have been conducted in a national representative sample of

three per cent of the primary school population at year 4 and year 8. These tests are conducted by specially trained teachers seconded from schools to undertake this work which is funded by the Ministry of Education. A wide range of skills is tested across all curriculum areas,

not just literacy and numeracy. The tests are conducted in a four year

cycle and cover three curriculum areas each year.

These are not just pen and paper tests and there is an emphasis on process

rather than product. For some tests children have to reach a consensus

with others. They are fun activities which the children enjoy. They are

taken out of class in small groups so the tests are not disruptive of the

class routine.

Full cohort testing which is being called for is not necessary as the information it would produce is already available through the National Education Monitoring Project (NEMP). The important facet is the use of

the information. What is needed is resourcing for professional development

to enable teachers to use the information so that they can better meet the

needs of their pupils.

The suggestion that full cohort testing be introduced led me to look at the

impact of earlier national testing of primary school children.

Testing of primary school children in the nineteenth century In the last quarter of the nineteenth century children in New Zealand primary schools faced standard tests to achieve a pass in every class. This testing had been the responsibility of the school inspectors employed

by the Department of Education, but in 1899 the authority to examine and

classify pupils up to Standard 5 was transferred from the inspectors to the

head teachers. The inspectors conducted the testing for Standard 6 (later

Form 2, now Year 8).

Secondary Schools Act 1903 When Richard John Seddon was Prime Minister and Minister of Education the

Secondary Schools Act 1903 was passed, making the Certificate of Proficiency a passport to free secondary education. Sets of examination

tests in English and arithmetic were supplied by the Education Department.

Each subject had a set allocation of marks.

- English

- Arithmetic

- Geography

- Drawing

|

|

400 |

|

|

200 |

|

|

100 |

|

|

100 |

At least 50% of the aggregate was required for a pass, with a minimum of

30% in English or arithmetic, and inspectors had to be satisfied that candidates had been “sufficiently instructed” in other subjects.

George Hogben as Inspector General In 1904 George Hogben who was headmaster of Timaru Boys’ High School was

appointed Inspector General. He was a vital and persuasive speaker and his

appointment was welcomed by the teaching profession as he believed in consultation with those actively involved in educating pupils.

Hogben believed that children learn better by doing than by book learning.

He abolished the standard pass in every class but continued the Certificate

of Proficiency. This examination was still conducted by the school inspectors. The subjects to be tested by examination were reading, spelling dictation, writing, composition, arithmetic, geography and drawing, and there was a general assessment of efficiency in other subjects.

Proficiency, as it became generally known, qualified pupils for free education at a secondary school or district high school, and soon functioned as a testimonial for school leavers.

The emphasis this gave to the Proficiency Certificate had not been Hogben’s

intention. He had written, “Slavery to formal examination tests has been perhaps one of the greatest obstacles to progress and accordingly

should be guarded against in future.”

The Certificate of Competency In 1904 an additional certificate was introduced – the Certificate of Competency. It was designed for those who did not pass the Proficiency

examination but had ‘fulfilled the requirements of some standard of education”. This entitled pupils to a place at the Technical schools. In

1913 it was decreed that for the Certificate of Competency pupils must gain

40% of the aggregate, with 50% in reading and composition and 30% in arithmetic. In 1916 endorsements were introduced to record special merit

in handwork or elementary science.

Pass marks raised for Proficiency In 1906 the pass mark for Proficiency was raised to 60% of the aggregate

with 40% in arithmetic and English. In 1918 the minimum mark for English

was raised to 50%.

In 1903 when the Secondary Schools Act was passed Hogben had expected a

third of candidates to pass, but in spite of the raised pass level in 1907

the pass rate was 59%, in 1908 it was 68%, and in 1912 it rose to 77.1%.

Why were pass rates so high? There were several reasons for the pupils’ success in the Proficiency tests.

First, parents wanted their children to get free places at secondary schools and there was pressure on children at home to pass their Proficiency.

Second, employers had come to regard Proficiency as a good indicator of the

level of education and skill of job applicants and it became an important

testimonial for employment.

Third, teachers were well aware of the demand for passes in Proficiency and

geared their teaching to achieving success in the tests.

Fourth, because a school was often judged by its pupils’ success rate in

Proficiency slower learners were often held back in classes further down

the school and so did not reach Standard 6 and sit the Proficiency test.

Promotion of brighter children? In 1924 it was suggested that brighter children should be pushed through

the classes faster. This idea was not popular in most schools as they liked their brightest Standard 6 pupils to be as skilled as possible so

that they would lift their averages in the examination marks.

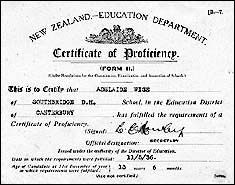

The system not too rigid When Adelaide Wise was sitting her proficiency at Leeston in 1935 she had

an accident which prevented her from sitting one examination paper. She

was allowed to go to Southbridge District High School in 1936 and complete

her proficiency test while there.

|

| Proficiency certificate awarded to Adelaide Wise in 1936 (Click here for a larger version) |

|

| Reverse side (Click here for a larger version) |

Proficiency examination finally abolished in 1937 The first recommendation for the abolition of Proficiency came in 1926. In

1929 the Competency Certificate was abolished.

From 1937 Proficiency was abolished and replaced by primary school leaving

certificates. This led to a broader approach to teaching programmes and

abolished the link between Proficiency marks and secondary education. No

longer did an external examination decide the type of secondary education a

pupil could receive.

In 1939 Peter Fraser, Minister of Education, stated that it was the Government’s belief that every child should have free education of the type

best suited to his need for as long as he could benefit from it.

How did people who had to sit Proficiency view their education?

Madge Dymond looks back My home life gave me security as we had loving parents who worked hard to

care for us.

I was born in Scotland in 1906, but the family came to New Zealand in 1914

so that my father could find work. My father had been trained as a plumber,

but could not find work in his own trade and became manager of a milk company. Even in New Zealand he couldn’t get any work as a plumber, so he

worked for the Christchurch Dairy Company. My mother was economical and a

good manager, so we never went without any necessities. I was happy to be

living in New Zealand. My main worry in life was sitting exams. I did

well in them but it was always a surprise as I had little self confidence.

In my schooldays I was in large classes. I remember writing on a slate and

rubbing it off with a sponge, and learning to write using what was called a

copybook. Printing was only on alternate lines and we had to copy exactly

the beautiful writing above. I really enjoyed that activity.

In the English syllabus I enjoyed writing compositions, but I didn’t really

like sentence analysis. Multiplication tables were recited every morning

and arithmetic and spelling were important subjects. Mental arithmetic

which we had to do quickly in our heads was a bugbear as I was afraid I

would not work out the answer in time before we were given the next question. History was mainly about England and centred around dates – 1066

and all that – and geography was about countries and facts like their capital cities and exports.

I was always stressed about exams although the teachers prepared us for

them very carefully. I passed my Proficiency and my parents did not expect

me to go straight to work, so I was one of the privileged girls of my generation and was able to go to secondary school for two years. Because I

wanted to study commercial subjects I went to Avonside Girls’ High School,

even though it meant two trips by tram get there. After two years there

I took a commercial course at Gilbys Commercial School.

I look back on my childhood as a fulfilling time except for the worry about examinations. However, my education enabled me to have a responsible office job which gave me the money to live an interesting life

as an adult.

Neil Clarke looks back. Neil, born in 1908, had a good opportunity to watch education at work as

his father was a school teacher and he also entered the teaching profession. He attended school in a number of South Canterbury townships,

then Lyttelton and then Addington, a suburb of Christchurch. In his view

the pupils received an excellent grounding in the key subjects of reading,

writing and arithmetic, and if they passed Proficiency and then left school

they had the basic skills to enter the workforce.

Neil taught at first in schools where pupils were being prepared to sit

Proficiency and later experienced the broader curriculum that was introduced from 1937. He found that when the rigorous standards of formal

learning demanded by that examination were removed teachers were able to

give their pupils a broader education, with more time for music, drama, art

and craft, science and physical education.

What will be the result if national testing is re-introduced into New

Zealand primary schools? Will it mean that pupils become more skilled in the three R’s? Or will it

mean that primary school pupils experience added stress in their lives?

Will the present wide ranging testing of a representative sample of primary

school pupils by replaced by limited pen and paper tests? Will teachers

work to a more restricted curriculum and spend less time developing children’s creativity?