Part 4 – Primary Education For Children In The Towns Dorothy – 22/11/00

You can read the previous part in the Growing up in New Zealand 1925 – 1950 series here, or read the articles from the original Growing Up in New Zealand series.

Preschool education Most children did not have pre-school education. A few attended private kindergartens. They remember kindergarten mainly as a place to play, but also having books and slates and having their first lessons in reading. Peter remembers being taught about the sun’s movement and how it caused shadows. Jo remembers that her sister, five years older than she was, taught her to read before she started school using a series called the ‘peg’ books.

During the Depression the Government decreed that children should not start primary school until they were six as an economy measure, but in 1936 the starting age was restored to five.

Walking or riding to school in the towns In the towns most children walked to school, often in groups, without accompanying adults. A number of children went to school barefoot. Some went on trikes when they were young and rode bikes as they grew older.

Once they reached school often the infants had a separate playground and from Standard one upward the playgrounds for girls and boys were segregated.

Judy remembers being collected from the house and riding in a bus to kindergarten and then refusing to leave the bus to go to the kindergarten.

David remembers that when he went to Fairfield Kindergarten in Garden Road in Christchurch, his sister took him on the back of her bicycle on her way to Rangi Ruru School. Fortunately the roads were sealed so the journey was smooth.

For Anna there was a walk of about a mile to the first primary school which she and her sister attended in Auckland, and a journey across town by two trams to the school they next attended. In Christchurch later they had to take a trolley bus or diesel bus and then a tram. Later they cycled to school.

I remember that when we lived in Roslyn, a hill suburb of Dunedin, my friend and I usually walked downhill to school with a neighbour who was walking to work, but we were not nervous about walking through the town belt of trees on our own. To go home quickly for lunch we would ride the Roslyn cable car. The cable car was also a lifeline in snowy weather as it was the only transport which could get up and over the hill when ice or snow was making the roads unsafe.

Jane lived in Wadestown and was allowed to walk three quarters of a mile to kindergarten alone.

Boarders at girls’ schools going from the hostel to school walked two abreast in ‘crocs’ (crocodile formations).

Heating Many schools were heated by hot water from the furnace passing through pipes and radiators on the walls. This heating was not effective and unless pupils were sitting in desks by the wall attending school in winter was a cold experience. Pot belly stoves were used in some schools but they were ineffective in rooms with a large class. Again these provided heating only for those close to the stove. Frank remembers a fireplace with a good fire in the Lyttleton school he attended, but this was unusual.

Lunches Most pupils took their own lunches from home. During the Depression some families had no money for cut lunches. There were no lunch rooms serving hot drinks in most schools. Pupils were sent outside to get some exercise and to air the classrooms in the lunch break unless it was raining, so the lunch break could be a very cold time in winter, especially for children whose families could not afford warm clothing.

School wear at primary school Very few state schools demanded that pupils wear a uniform. Girls wore dresses or a skirt and jersey. Boys wore shorts, even in the winter. In places like Naseby this often meant painfully cold knees.

|

|

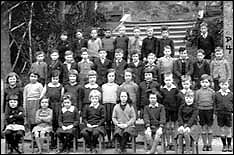

| All neat and tidy for the annual class photo |

Examinations important The atmosphere in the classroom was very different from today’s. Classes usually had forty or more pupils, mostly mixed, but often with girls sitting on one side, boys on the other. Although most of the people discussing this topic were not of the age to sit Proficiency we had examinations each term and took them seriously. We felt it was really important that we pass our exams. Failure was a real anxiety for the slower pupils because there was no social promotion from class to class. Some were held back in one class for two or more years. Many did not get above standard four.

Jane remembers the weekly tests on ‘basics’ on Fridays. "They had to be done in a special test book. On Mondays the results would be posted. Seating the classroom was based on these results, so that the pupils sat in order from the most successful down to the least. Those who had more than three mistakes in spelling or arithmetic were strapped on the hand. Our teacher was a vestige of the old system."

From about standard five at the convent school Anna attended in Christchurch the end-of-year exams were marked externally by teachers at another of the Order’s colleges in a different town.

The teaching methods were very different with more rote learning, not the stimulus and exploratory techniques of today’s classrooms. There was less group work and individual teaching.

Anna recalls, "Sometimes for ‘tables’ in standard three we lined up in the aisles between the desks. As a question was answered one moved to the end of the row. If an incorrect answer was given one stayed at the front until the turn came for another question. The process was run through a number of times. The incentive to learn one’s tables was great to avoid holding up one’s team."

Discipline With little of the pupil participation that is seen in today’s classrooms pupils were meant to speak only when spoken to. Both boys and girls, were strapped with a leather strap on the hand for a variety of reasons – both for poor work and for what was deemed misbehaviour. Judith remembers being strapped on her first morning at school because the girl next to her claimed that she had been talking. Being smacked around the legs with a ruler was a common punishment. If the pupils were restless the whole class would have to sit with their hands on their heads or their arms folded – which put an end to fidgeting.

When one girl aged five played truant and told her mother she had been allowed to go home as a reward for good behaviour her mother told the teacher and her punishment was to stand in the corner facing the wall until the lunch break – which she declares cured her of playing truant and of telling any but little white lies.

Left handed pupils Frank recalls, "For three years I attended the local school. I remember the teacher waiting with a metal ruler for me to take up the pencil in my left hand. If I did she dealt with me very severely hitting me across the knuckles. I had to spend two years in standard one, but luckily with a different teacher in the second year. My father was so furious at the treatment I was receiving that he sent me to my uncle and aunt in Invercargill when I was eight years old. "

There is no doubt that such children suffered greatly from being forced against their will to change from left-handed to right-handed writing. Frank continued to write with his right hand which was fortunate.

When he was in Invercargill he had a very tough master who had a four-tailed strap for discipline. Everyone was so scared that it was rarely used.

After that he returned to the former school.

Writing materials In the earlier years of this period pupils worked on slates. Tom remembers using them. "The slates were smooth slabs of natural slate about 20 x 25cm surrounded with a wooden frame. We wrote on them with a slate pencil, a rod of slate about 6mm in diameter, originally about 15 cm long. The slates came clean with a damp rag. From slates we graduated to pencils and eventually to ink with dip pens."

School desks had a round hole for the ink well and ink monitors were appointed for each class. They had to keep the ink wells filled – a messy job for those who didn’t have a very steady hand. From about standard 4 (present year 6) pupils worked in ink instead of pencil, and it was very hard for some of us to keep our work free of blots and smudges. Blotting paper was an absolute necessity! Girls with long plaits sometimes had the ends dunked in the inkwells of the desks behind!

Writing was done with nibs fitted into a pen holder. Nibs came in various sizes and broad nibs were used for special printing. There were no ball point pens. Most people had to wait until they were at secondary school before they were given a fountain pen. During the war such things were scarce and one woman remembers using one given to her mother on her twenty first birthday, putting it in her pocket and then leaning against the arm of the seat in a bus and breaking it. She felt a terrible sense of guilt and loss, especially when it was so hard to get a new one.

Work was done in exercise books, so it was not possible to have a fresh start on a new page as it is when using folders with loose sheets. With the paper shortage during the war there were stict rules for economising on paper. Margins were to be written in and the books were to be filled without gaps.

The leaving age had been thirteen until 1901 when it was changed to fourteen. In 1944 it was increased to fifteen.

The School Journal This publication which first appeared in 1907 featured prominently in the programme in most classrooms. It contained excerpts from English literature, and articles about history and geography, mainly relating to the British Empire, nature study, civics and moral instruction. It was well after 1950 before New Zealand themes and writers predominated.

Honouring the flag Barbara T recalls the whole school standing outside school each morning before lessons began while the headmaster would raise the New Zealand flag on a flagstaff and they all sang ‘God Defend New Zealand’.

|

|

| School Assembly |

School milk and apples In 1937 free milk for primary school children was introduced throughout the country. New Zealand was the first country in the world to introduce the scheme which lasted for thirty years. The milk was distributed usually at morning break. It was not pasteurised or homogenised and there was a layer of cream on the top. All had vivid memories of the bottles with cardboard tops and the perforation in the middle to be pushed open to allow for the straw. There were no refrigerators and in some schools the crates of milk were left sitting in the sun and the milk was less than pleasant to drink and possibly a danger to health.

Ron recalled that at his school the boys who were milk monitors drank all the milk in the leftover bottles and after a time there were no players light enough to play in the rugby teams for boys under five stone (30kg).

Joe recalled that one of the perks for the prefects was drinking the cream off the top of the surplus bottles of milk to provide the skim milk for mixing with the tennis court marking materials.

During World War II an apple was provided daily for each pupil from orchard surpluses, mainly Jonathan and Red Delicious.

Music Singing played an increasingly important part in the primary schools and many people have vivid memories of singing in music festivals where individual choirs presented their own items and then joined for the massed singing. Barbara T remembers the St Patrick’s concert at which the choirs from the Catholic schools sang together dressed in long white muslin frocks with green shamrock crowns on their heads.

Go on to part five!